How Much Water Can You Pour Into a Tesseract?

April 24, 2017

The Red Box.

An artist’s

conception of the two boxes now on your kitchen table.

Two empty boxes now sit on your kitchen table. The one on the left is red, the one on the right is blue, but near as you can tell they’re otherwise identical. For the moment let’s focus on the red box. It is a cube, so its edges are identical, and each edge happens to be one meter in length, or about three feet. Now a simple question: How much water could you pour into this red cube?

“Well, a cubic meter of water,” you reply, which is the volume of the cube. And you’re not wrong, of course, but what does that look like? In more everyday units, a cubic meter corresponds to 1,000 liters. That’s two-liter bottles of soda, or if this makes more visceral sense to you, about bottles of wine. That seems a lot.

And because water is so dense, about kg/m³, this means the topped-off red box weighs a metric ton, or lbs. A metric ton! This seems wrong. An 8 oz glass of water weighs hardly anything at all, yet a three foot cube filled with water, which cube fits comfortably on your kitchen table, weighs a ton? It’s true, but why is it surprising? The shock stems from our faulty intuition about how volume scales with size. That 8 oz glass of water seems smaller than the box, sure, but not that much smaller, not so much smaller that it weighs half a pound to the box’s metric ton. But in fact the volume is quite a bit smaller. While the red cube boasts a volume of 1.0 m³, that eight ounce glass of water is an ignominious m³, or times smaller, volume-wise.

If we make the red cube larger, things get predictably worse. Doubling its edge does not double its volume, but rather increases it by a factor of . A two-meter cube filled with water would weigh eight metric tons, or more than lbs, and would require two liter bottles to fill it. This is now starting to be a structural issue for your kitchen table, your kitchen, and possibly your marriageHence we will perform this experiment only in our minds. .

That three in comes about because the red cube resides in three spatial dimensions. The volume of a cube with edge length is given by,

If we increase the size of the cube by a factor of , its volume increases by a factor of , or . That power of three is the explanation for the alarmingly vast difference between the weight of that glass of water and the weight of that red box, and is fundamentally tied to the number of dimensions of the spacetime in which we live.

The Blue Box.

But now to the empty box on the right, the blue one. In all obvious respects it is a one-meter cube like its red compatriot. Except it’s not. This is no blue cube at all, but rather a blue hypercube. Or a tesseract. Or a four-dimensional box. We will use these terms interchangeably, and we will not worry how I came to possess the thing, what strings I pulled, what favors I called in, or how I got it into your kitchen.

Limited as you are to three spatial dimensions, you might well walk past the blue box without realizing it is special. After all you cannot detect, in three dimensions, how this box pokes into the fourth. But it does nevertheless. Its volume is not m³, but rather m⁴. In general, a hypercube with edge length has a volume is given by,

Now as before, we ask the question: how much water can we pour into this thing? How many of those two liter soda bottles, or those ml wine bottles will it take to fill this blue hyperbox? If you turn on your kitchen faucet and start filling bottles, how much municipal water will you store in that one-meter tesseract? What would such a thing weigh?

This is the sort of question that strains the imagination and keeps a certain type of person from a good night’s sleep. We rightly wonder, Does the Question Even Make Sense? Water being a three-dimensional fluid lives in the space defined by the , , and -axes. The tesseract on the other hand is a four-dimensional beast, residing in the hyperspace defined by the , , and and, let’s say, -axes. How do we make sense of this? Let’s attack the problem step-by-step. First, what exactly do we mean by tesseract?

What Is a Tesseract?

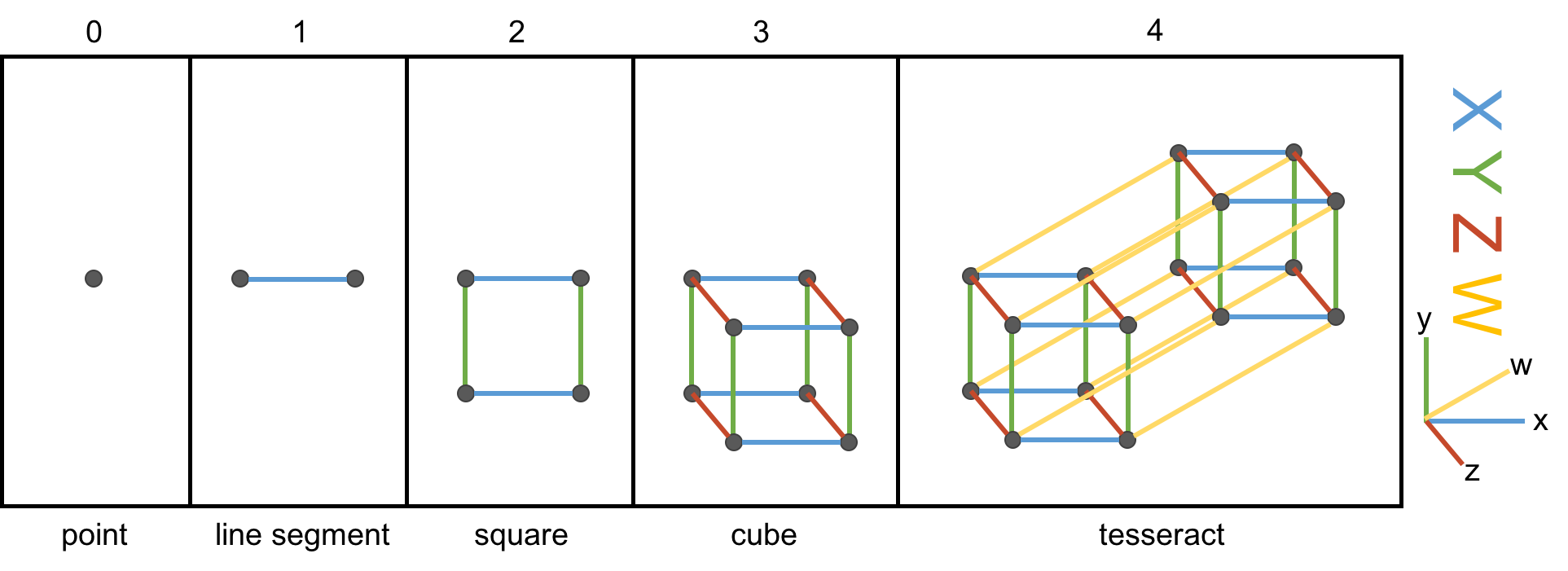

A tesseract is the four-dimensional analogue of the three-dimensional cube. It is to a cube what a cube is to a square, what a square is to a line segment, or what a line segment is to a point. The figure below may or may not help you make sense of this.

We begin, simply enough, on the far left, with a single point, an object of zero dimension. We can think of it as a zero-dimensional cube. To create its higher-dimensional counterpart, we drag the point along the blue -axis, creating a line segment, which we can think of as a 1-dimensional cube. In an analogous fashion, we drag the line segment along a perpendicular dimension, the green -axis, to trace a square (a 2-D cube) in the - plane. If we drag that square along the red -axis, we trace a cube (that is, our familiar, everyday 3-D cube) in the -- space. The cube in the third panel is not really a cube, of course, since the screen is only two-dimensional, but rather a projection or shadow of a cube.

But now the hard part, the impossibleIf you have an iPhone, I recommend the excellent app called The Fourth Dimension, which builds intuition on these matters by allowing you to interact with, rotate, and otherwise muck around with hypercubes. leap: to create a hypercube, we must drag our cube along a dimension perpendicular to each of the , , and -axes. We’ll call this the -axis. Human imagination, or at least mine, is limited, which makes the matter of visualizing a 4-D cube a bit maddening. The far-right panel above nevertheless illustrates the hypercube — the object we obtain by dragging the cube along the yellow w-axis. We’re not really seeing four dimensions here of course. Just as with the cube, we are merely seeing its two-dimensional shadow.

An animated projection of a rotating hypercube. It makes sense if you think about it long enough.

Consider the animation to the right. It shows a projection of a hypercube as it rotates through the -dimension. Though unintuitive at first, you may be surprised at the insight you can gain by trying to understand why it is doing that. On the other hand, if you fail, you will be delighted to know that we need not be able to visualize four-dimensional objects in order to reason about them, as we’ll see below.

So much for the hypercubes. What about the water?

Water, Simplified.

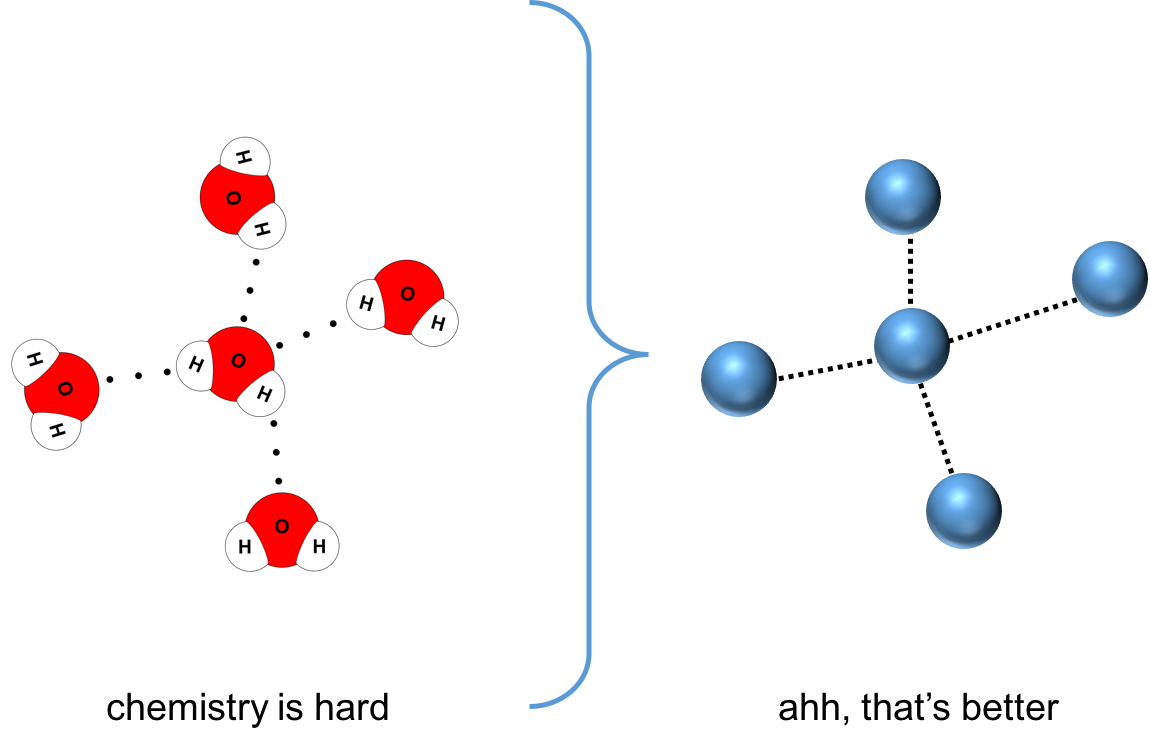

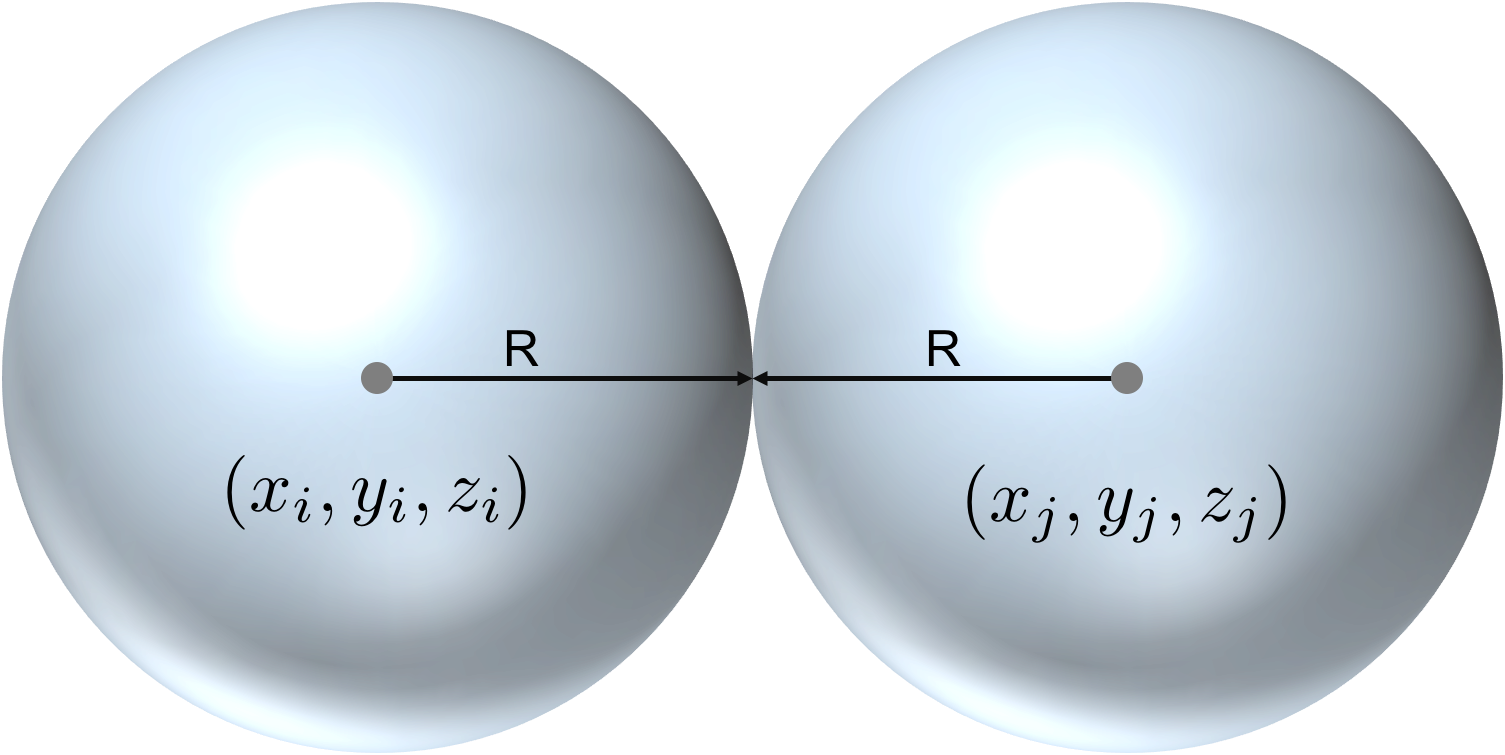

Water is a molecule comprising two hydrogen atoms and an oxygen atom, but we’ll not be too concerned with its chemistry beyond a few salient properties. In fact, we won’t worry about the structure of the water molecule at all but, like proper physicists, treat the water molecules as spheres. From here on out, we’ll think of the water molecules as hard spherical masses with a fixed radius, R, as illustrated in the diagram below.

In three dimensions, the position of every water molecule is specified by three coordinates. Molecule , for example, can be found at position . Another molecule, , will collide with the first if the following is true:

That is, the two molecules will collide if the Euclidean Distance between their centers is less than twice their common radius.

Thinking about water in this way is useful because we can readily segue to four dimensions. In that case — inside the tesseract, for example — we must specify four coordinates, not three; i.e., . And now collision between two molecules occurs if,

The difference here being we calculate the distance between molecules using the four-dimensional Euclidean metric, rather than the three-dimensional one.

Now an important side note: aside from this extra coordinate and its geometric implications, we assume that the introduction of a fourth dimension does nothing to substantially alter physics. In fact, adding an extra spatial dimension will certainly muck up our chemistry, perturbing quantum mechanics, changing the nature of water, altering its rotational and vibrational modes, absorption spectra, effective radius, and so forth. We could explore extensions to standard physics such Kaluza-Klein theory, string theory, and M-theory, which posit or demand the existence of additional spatial dimensions, and which might provide insight into how the underlying physics is thereby perturbed. But we shall not be heading down those rabbit holes here. We will focus exclusively on on the geometry of the problem.

Recall that a mole is a unit of measurement corresponding to the number of representative particles in a chemical substance equal to the number of atoms in 12 grams of Carbon-12. That number is known as Avogadro’s constant, which has a value of just over 602 sextillion mol-1; you can regard it as a conversion factor of sorts between the atomic and macroscopic worlds.

In that case, here is all the chemistry we’ll need. The effective radius of a water molecule is about nm. It has a mass of 0.018 kg/mole, which means that a collection of water molecules weighs 0.018 kg. Under everyday conditions, as we’ve already noted, liquid water has a density of kg/m³.

In three dimensions, we find that the volume of a single water molecule — what is typically known as its specific volume — is very tiny:

where we’ve used the usual equation for the volume of a sphere in three dimensions. The red box, that ordinary three-dimensional cube, when filled with water, weighs kg. This means it contains kg/( kg/mole) moles of water, or around individual water molecules.

The total volume occupied by all these molecules (given the specific volume of a water molecule à la Eq. ), is:

And here we find a surprise. We have filled a box with water but find the total volume occupied by the water molecules amounts only to 30% of the total volume! Water, it seems, is 70% empty space.

Why all that space? The reason is that water molecules are not densely packed like oranges at a grocery store. They’re not constantly in contact with one other, but are free to jiggle and collide — and this leaves a lot of empty room between. Chemists define the packing fraction of a substance, , as the total volume of space that is occupied by the constituent particles. The packing fraction of water is therefore . Gaseous water vapor, on the other hand, which is far less dense than liquid water, has a packing fraction on the order of .

One may find slightly different values for the effective radius of water kicking around in the literature. Do not let this ruin your day; a slightly different effective radius implies a slightly different packing fraction in order to obtain the observed density. More important is the order of magnitude of the quantities involved.

We may write down a relation for the total number of molecules that can be stored in a box of given volume in terms of the specific volume of the constituent molecules and the fluid’s packing fraction:

To put this in words: to determine the total number of particles in a box, we simply divide the total effective volume we are filling, which is , by the volume occupied by a single molecule, . Importantly, this relation holds for any number of dimensions, so long as we compute volumes (or lengths, or areas, or hypervolumes) consistently for both box and molecule.

A Brief Digression: Packing Fractions.

Let’s take a quick moment to talk more about sphere packing, the object of which is to find the arrangement of spheres that occupies the largest possible proportion of a space, or to describe how spheres, when left to their own devices and subject to various constraints, manage to arrange themselves.

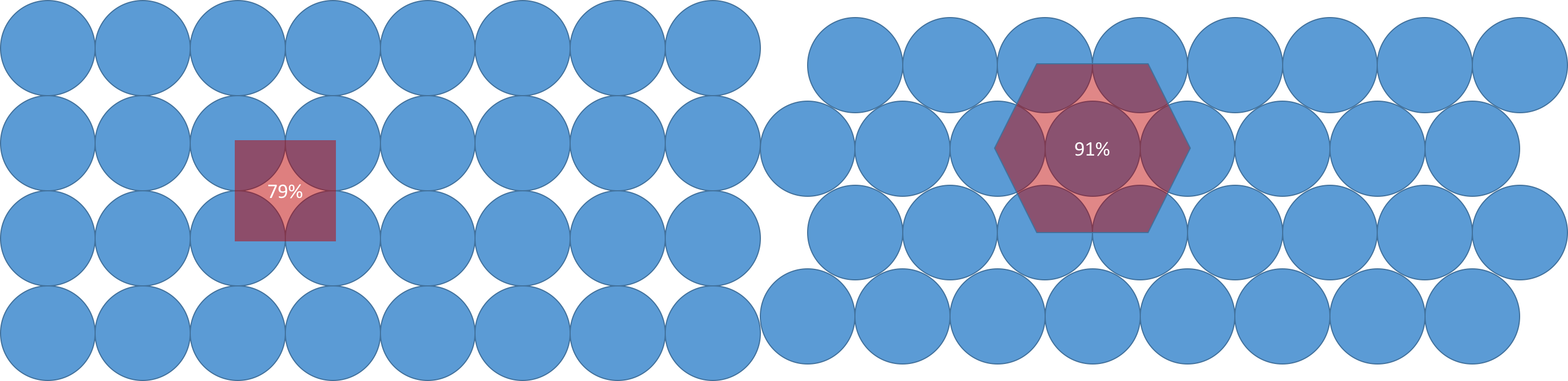

The illustration below shows two different packings of 2-D spheres in the plane, so: circle packing.

The arrangement on the left, known as a square packing because the circle centers are arranged in a square, has circles occupying 79% of the plane. The packing on the right, known as a hexagonal packing, which is provably optimal, has circles occupying 91% of the plane. In one dimension, the best packing ratio for spheres (which on a line is just line segment packing) is 1. In three dimensions, the best packing fraction drops to 0.74. In dimensions higher than three the sphere packing problem remains unsolved—except, thanks to the exploitation of certain symmetries, in dimensions eight and twenty-four.

The point of this discursiveness is that spheres pack differently in different dimensions, even if they’re not being optimally packed, and if we’re going to pour water molecules into the fourth dimension, we should worry at least a little bit about how they might decide to arrange themselves once there. As a general rule, as we increase the dimension of the space, the packing fraction of spheres decreases precipitously, at least according to computer simulations. In one investigation, the average random packing ratio scales with the dimension, , according to the following empirically determined formula,

For , we find that the packing ratio is . For , it becomes , a 25% decrease. But a caveat: these results were derived for a specific packing scenario known as disordered jammed spheres, which is not exactly the scenario at hand.

Water molecules are not in constant contact, but their mean free path (i.e., the average distance a molecule can travel between collisions) is less than the average intermolecular separation. It would be an interesting exercise to simulate how spheres pack in this scenario, and I leave this as an exercise to the motivated reader, but at this point we take the possibly dubious and certainly hand-wavy step of assuming that the packing fraction of water in four dimensions will be discounted according to the above formula. That is, if the packing fraction of water in three dimensions is 0.3, then in four dimensions it will be about 0.25.

This may not be quite right, but as we’ll see, for all this garment rending, the precise packing fraction will not make too much of a difference. In four or five dimensions, at least, it is on the order of unity.

Let’s Do It: Pouring Water Into the Tesseract.

When we pour our first liter of water into the blue box, what happens? The water molecules, entering the box, find themselves liberated from the confines of three-dimensional space; they acquire a new coordinate, , and can suddenly move in the -direction. Their specific volume, too, changes. They are still spheres defined by a radius of nm, but in four dimensions, volume is no longer given by Eq. . It must be computed as the volume of a four-dimensional hypersphere. That volume is given by,

We’ll call this water’s specific hypervolume. Note that it is many orders of magnitude smaller than its three-dimensional analogue (though understand we’re not comparing apples to apples here, but to ).

We are finally in a position to calculate the total number of water molecules we can fit into your tesseract. Using Eqs. and and with we find,

All of Lake Zurich could be poured into that four-dimensional hypercube on your kitchen table.

That is something like moles of water, which would weigh about billion metric tons, and, in three dimensions, occupy a cubic mile. For comparison, that is roughly the size of Lake Zurich, in Switzerland. A cubic mile of water! Sitting on your kitchen table! Recall that it took 500 two liter soda bottles to fill our red 3-D cube; it would take over two billion such bottles to fill our blue tesseract. It seems there is a lot of extra space in four dimensions.

Now that we know how to calculate these things, we can run wild. Suppose that instead of the one meter hypercube, we had a more reasonably sized, one inch, pocket-sized hypercube? How much water can we fit in one of those? Running the same calculations above with a hypervolume of yields an effective volume of . This is nearly the volume of an Olympic-sized swimming pool. And you could carry it around in your pocket, except that it would weigh metric tons.

Quite expectedly, hypervolumes grow even faster than 3-D volumes as length scale increases. If we had a four-dimensional Olympic swimming poolThat is, an ordinary three-dimensional Olympic swimming pool that happens to extend into the fourth dimension a distance equal to the (3-D) length of the pool. , for example, we could accommodate the entire Black Sea. Such is the power of powers of four.

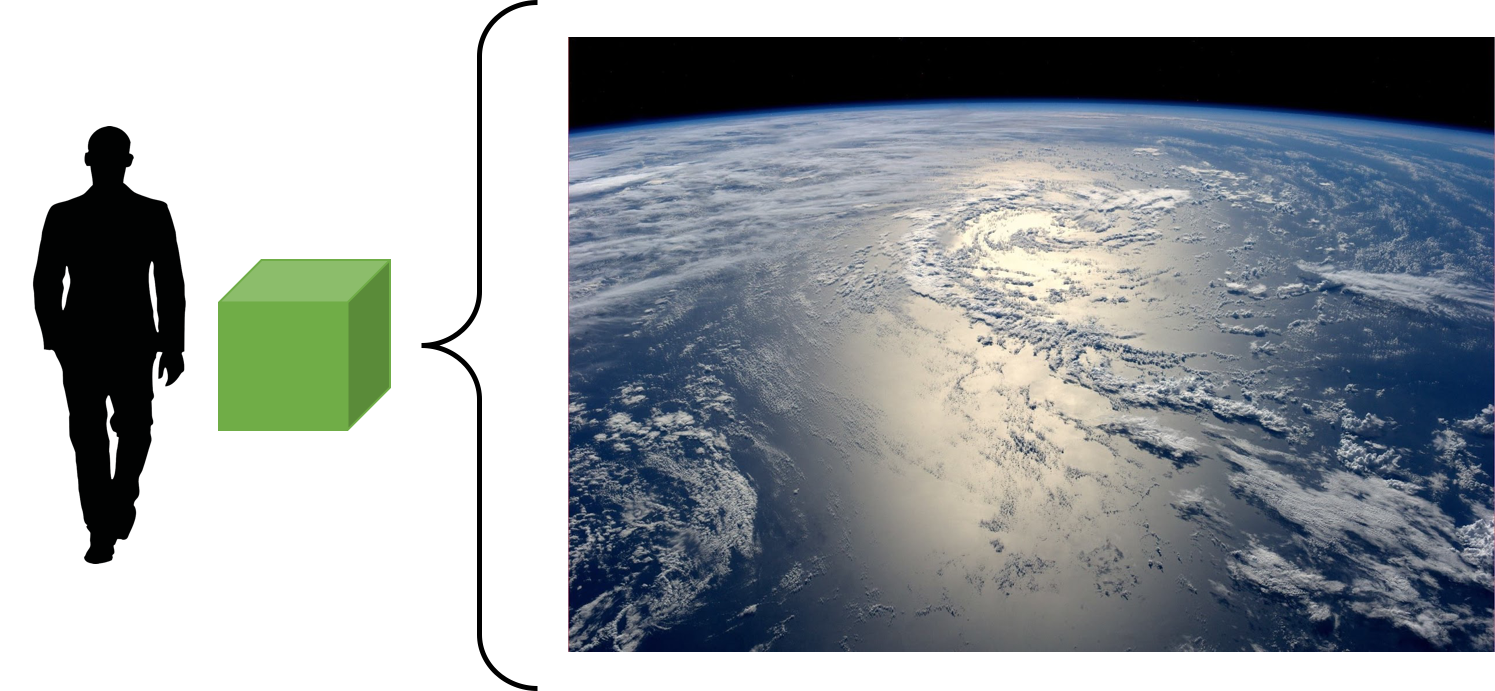

And since we’re bending the rules of our Universe anyway, why not consider even higher dimensional containers—a five-dimensional box, perhaps? We should expect even more dramatic storage capacities. If I were to loan you my green, five-dimensional hypercube, how much water could you fit in that? I’ll leave it to the reader to calculate the details, but it would exceed , enough to accommodate all the water on Earth, and then some.

A five-dimensional hypercube with one meter edges could easily contain all the water in all the oceans on Earth.

On your now very distressed kitchen table.